A Civil War, Then the Long Limbo of Life as a Refugee

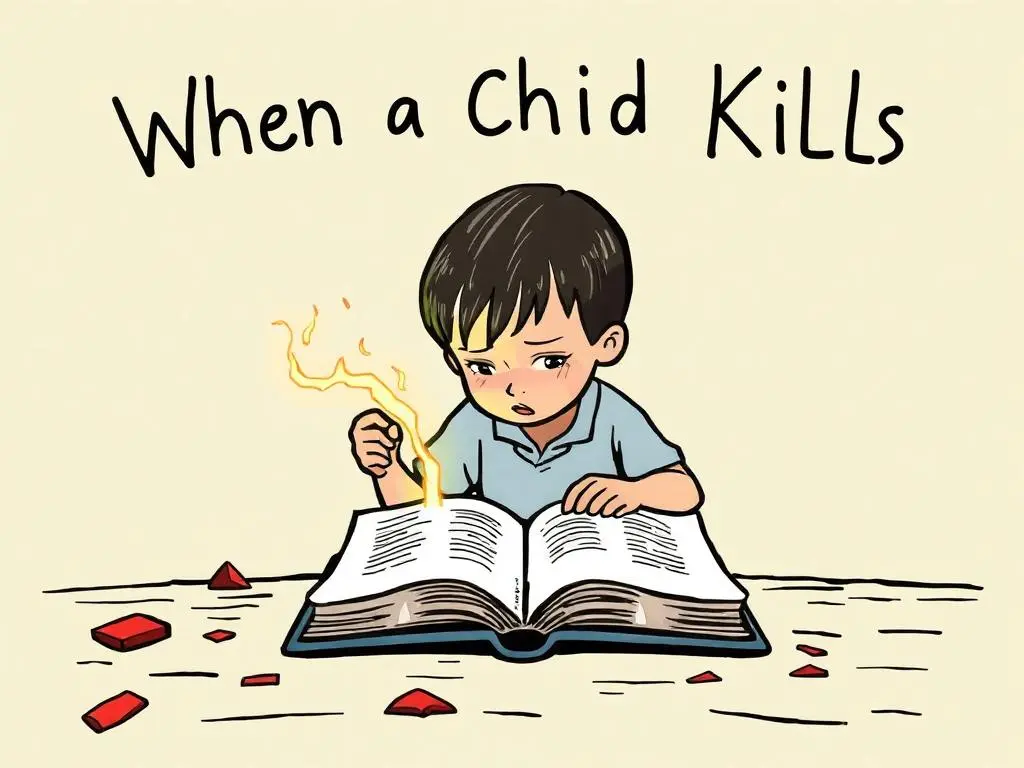

Late in WHEN STARS ARE SCATTERED (Dial Books for Young Readers, 264 pp., $20.99; ages 9 to 12), 17-year-old Omar Mohamed is asked to write a paper on “What It Means to Be a Refugee” for what he complains must be the 20th time since he started school six years earlier. Consider this fantastic graphic novel to be his 21st — and definitive — word on the subject. Written and illustrated by the Newbery Honor winner Victoria Jamieson (“Roller Girl”), based on extensive interviews with Mohamed, now a U.S. citizen who aids refugee resettlement, the book chronicles young Omar’s real-life experiences during the 15 years he spent in the U.N.-run Dadaab camp in Kenya.

What does it mean to be a refugee? For Omar, it means waking up with nightmares about seeing his father shot. Taking care of his nonverbal younger brother, Hassan, who suffers from seizures. Searching for their mother, lost in their escape from Somalia’s civil war. Endlessly sweeping the dirt floor of their tent. Playing soccer with a ball made of plastic bags. Praying. Navigating the complicated social structure of the camp. Doing anything he can to forget his persistent hunger. Enjoying the rare distraction of a religious holiday. And, after he is at last persuaded to leave his brother in the care of their foster mother in the camp, going to school.

But mostly what Omar does is wait. He waits in line for water. He waits in line for food. He waits to be interviewed by the U.N. to see if he and his brother are candidates for refugee resettlement in someplace like America or Canada or Sweden. And when he and Hassan finally do get an interview, they have to wait another four years for the next round of interviews that will actually decide their fate. “Every single person in this camp was waiting for something better. Waiting. Waiting. Waiting,” Omar laments. “How long can you wait before you lose all hope?”

Jamieson and Mohamed don’t shy away from the harder realities of life in the refugee camp. A predatory gang of kids steal Omar’s and Hassan’s clothes when they wander out of their own neighborhood. An unforgiving desert surrounds the camp and keeps them from leaving. Men with no jobs and no purpose loiter in the market chewing khat leaves to escape their dreary existence. There is uncertainty, fear and crushing boredom, and some people take their own lives to escape it all.

The author and her subject also show how much more hopeless life often is for women in these camps. The other boys make fun of motherless Omar for doing “women’s work” like water-collecting and cleaning and child care, and he’s not even expected to run home during his school lunch break to prepare food for his family the way the girls are. His friend Maryam — easily the best student, girl or boy, in the entire school — dreams of getting a scholarship to study in Canada and eventually bringing the rest of her family with her. Instead Maryam’s father pulls her out of middle school and marries her off to an older man for more immediate financial gain. By book’s end, as Omar is graduating from high school, Maryam has a chatty preschool daughter of her own, and another child on the way.

But for all its grim authenticity, “When Stars Are Scattered” is ultimately optimistic. “In a refugee camp, you are always reminded of the things you have lost,” Omar says. “It is a valiant and agonizing struggle to focus not on what you have lost … but on what you have been given.” And what Omar and his brother have been given are people who care about them, from their foster mother to their friends to their U.N. social workers. Jamieson’s lively, charismatic art and Mohamed’s remarkable life story will make young readers care about Omar and Hassan — and perhaps do something to help the millions of other refugees still languishing in camps around the world.